On the list of things for which I am grateful lately, spending ten days with my husband and his family on the beach of Key Biscayne ranks near the top.

A highlight of the vacation has been the extended time I’ve given to one of my favorite activities: reading. Among the numerous books I’ve read on this trip is one I received as a gift (thank you, Evan!) just before departure: The Other Shore, by Buddhist master Thich Nhat Hanh.

By the time I reached the end of the introduction, in which Thich Nhat Hanh explains the rational behind his translation and editorial comments, I knew I would enjoy this read:

I hope you enjoy practicing and chanting this new version of the Heart Sutra in English. On the twenty-first day of August in 2014, at around three in the morning, just after I finished the translation, a moon ray penetrated my room.

The Other Shore, p. 22

How delightful! No commentary on the moonbeam, no interpretation that it is some sort of cosmic affirmation of the author’s work. Just simple noticing: there, a moon ray!

Studying this text transported me back to my undergraduate days majoring in comparative religion. Though my college experience invited me to explore traditions and philosophies with an academic lens, I couldn’t help but juxtapose those vocabularies with my native (and continually chosen) Jewish one. Reading The Other Shore with the same mindset thus felt like familiar ground.

The central notions of the Prajñāpāramitā-hṛdaya Sūtra (c. sixth century CE), which is commonly called the Heart Sutra but Thich Nhat Hanh titles more literally as “The Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore,” are that of “interbeing” and its companion “emptiness.” Consider the following:

If you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating in this sheet of paper. Without a cloud, there can be no rain; without rain, the tree cannot grow; and without trees, we cannot make paper. The cloud is essential for the paper to exist. If the cloud is not here, the sheet of paper cannot be here either. So we say that the cloud and the paper inter-are.

The Other Shore, p. 27

In my undergraduate studies, I encountered this notion, central to Buddhist traditions, as “co-arising.” It means that nothing happens on its own. Everything, like the sheet of paper, comes into being only in relation to everything else that also comes into being. This extends to you and me: our bodies exist only because the clouds and rain and trees exist. Same goes for our senses, perceptions, and thoughts, which arise together with our bodies and in turn affect how our bodies interact with the rest of the world. Everything “inter-is,” and we are co-creators.

Looking even more deeply, we can see we are also in the paper. This is not difficult to see, because when we look at a sheet of paper, the sheet of paper becomes the object of our perception. It is becoming more and more clear to neuroscientists that we cannot exactly speak of an objective world outside our perceptions, nor can we speak of a wholly subjective world in which things exist only in our mind.

The Other Shore, p. 28.

Described one way, the piece of paper is not paper at all; it is merely a collection of molecules with a certain form. Only by virtue of our grasping it as paper does it attain the reality of being paper. Nothing has existence independent of everything else. Hence interbeing’s companion: emptiness, that everything is empty of a separate, essential self. The sheet of paper is empty.

[The paper] cannot just be by itself. It has to inter-be with the sunshine, the cloud, the forest, the logger, the mind, and everything else. It is empty of a separate self. But empty of a separate self means full of everything.

So our body is empty of a separate self but full of everything in the cosmos. Our feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness are all empty of their own separate nature and at the same time full of everything that exists.

The Other Shore, p. 33

As I once read in Journey of the Universe by Brian Thomas Swimme and Mary Evelyn Tucker (another gift––thanks, Lily!): we are the universe in the form of human beings. Flowers are the universe in the form of flowers. And when we appreciate the beauty of a flower, we are the universe contemplating itself.

There are few better places to be a universe-in-the-form-of-a-human contemplating my own interbeing and emptiness than sitting at the universe-in-the-form-of-the-ocean. It’s precisely those times when we experience awe before a wide expanse that we tend to feel “part of it all.”

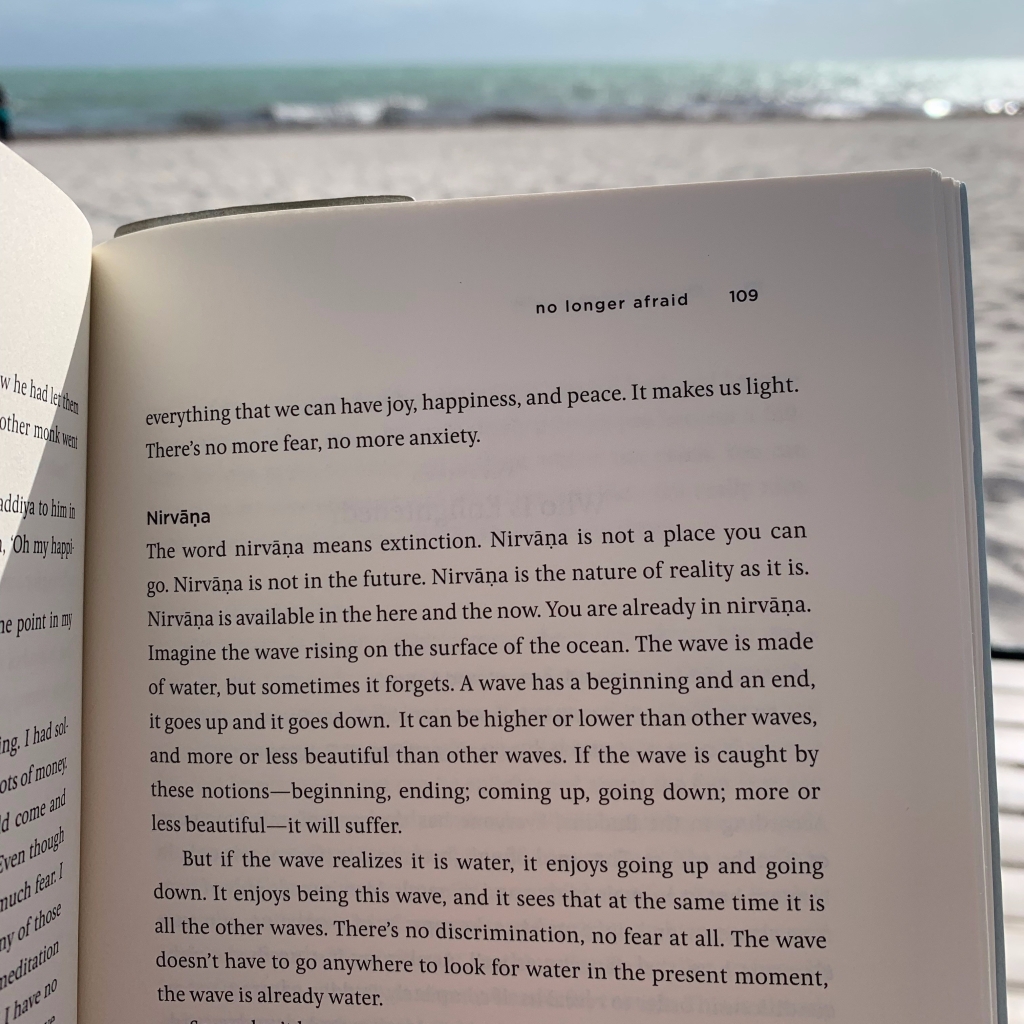

Near the end of the book, I was delighted to arrive at an image I knew from years ago: that of the wave that is water. Thich Nhat Hanh offers it in his discussion of nirvāṇa, the state of truly realizing the interbeing and emptiness of everything, in which all attachment and suffering give way to peace and wholeness.

The wave is made of water, but sometimes it forgets. A wave has a beginning and an end, it goes up and it goes down. It can be higher or lower than other waves, and more or less beautiful than other waves. If the wave is caught by these notions––beginning, ending; coming up, going down; more or less beautiful––it will suffer.

But if the wave realizes it is water, it enjoys going up and going down. It enjoys being the wave, and it sees that at the same time it is all the other waves. There’s no discrimination, no fear at all. The wave doesn’t have to go anywhere to look for water in the present moment, the wave is already water.

The Other Shore, p. 109

My first exposure to this metaphor came on Saturday night, June 12, 2010. It was Havdalah during staff training week at GUCI, and the whole camp staff gathered in the outdoor shelter called the Mercaz Chevrah. We sat in concentric circles, singing the prayers to mark the end of Shabbat––and we kept on singing soulful songs.

Dan Nichols led us in “Sanctuary,” an originally Christian melody that lends itself to building harmony upon harmony. As we hummed the tune and he strummed the chords, he told a story of two waves, a little one and a big one. The little wave notices the big wave is crying. The big wave is sad because it can see the waves ahead of it reaching the shore, crashing, and dying. The little wave comforts the big wave: “You’re not a wave. Your water.”

Then we sang the words:

Lord, prepare me to be a sanctuary,

Pure and holy, tried and true.

With thanksgiving, I'll be a living

Sanctuary for you.

Nowadays when I sing this melody, I often couple it with one of my favorite lines from the Torah. It’s the rational God offers for commanding the Israelites to construct the Tabernacle:

וְעָ֥שׂוּ לִ֖י מִקְדָּ֑שׁ וְשָׁכַנְתִּ֖י בְּתוֹכָֽם׃

And let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them.

Exodus 25:8

After reading The Other Shore, pairing these words with that story of the waves, and now linking it to the line from Exodus, I’m seeing the passage perhaps the way the mystics do: Let me be a sanctuary, empty of self-existence, and full of All-That-Is. It’s a new understanding, one that co-arises with me being on the beach, with Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings, and with the vocabularies I’ve built so far.

One more thing that happened when I read The Other Shore on the beach…

I may not have an Instagram account, but now that I write Sivuv I have developed an Instagram-like mindset: I often consider how capturing a picture of a scene will be useful on the blog. So I thought a picture of the wave metaphor as it appears in The Other Shore, with actual waves in the background, would be quite fitting. The above shot is my first attempt. The second did not go so well.

A bit of background: I have been using the same bookmark in nearly every book I’ve read since the spring of 2005. It’s a leather bookmark I bought in Florence, Italy, on a high school trip to Europe. This bookmark is one of my most cherished possessions.

After I finished reading The Other Shore, I thought to try for an even more spectacular shot juxtaposing the wave passage with the ocean: a panorama with the text on the left and the waters opening out to the right. I tucked my bookmark in the back of the book, walked closer to the water, and tried to hold the book open to the appropriate page in my left hand while fiddling with my iPhone camera in my right.

Remember the kite surfers? It was a very windy day.

I could not get the book to stay open. The pages fluttered wildly; I could barely hold the book with my one hand, let alone keep it on the correct page. After a futile minute, I gave up and started back to my chair.

The bookmark was gone.

I immediately weighted the book down with my water bottle and started pacing back and forth along the beach. The wind was blowing inland, and the bookmark is not a kite. It couldn’t have gone far. But it is also light gray and flat, not too distinct from the sand, especially if it had already started to be buried.

Back and forth, back and forth I walked. I did not want to lose the bookmark. At the same time, I tried to tell myself, The bookmark and I had a good run for 13 and a half years. It’s only an object.

And as I scanned the sands, I couldn’t help but think a very Buddhist thought: Well, this is what attachment gets me: suffering, when the object of my attachment inevitably is gone.

Finally, there it was. Maybe I found it only because I was ready to give up and let it go. Maybe I needed that moment to integrate the teachings of The Other Shore into my actual life with rather low stakes. Maybe it was cosmic affirmation.

I loved reading your blog, Sam! Ah, to be the wave and the water in all its seasons and weather.

Love, A beach baby.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Sam,

I responded to your post and for some reason, the form did not accept my response – the gist of which was “thank you for transporting me from Skokie, IL (where I am teaching at an iCenter seminar) to Key Biscayne, FL. I agree that the photos add a dimension of visual intelligence and it seems as though you have many good friends – some of whom are books!

בברכה

Jan

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a beautiful piece. I don’t know if you meant this to be a book review, but it reads like one. And a really memorable one. I love the picture inserts too. Just lovely!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike